Facebook Sperm Donors and the Politics of Reproduction

I watched this British documentary on sperm donors to see if there was something that would be useful for a subject I teach on critical thinking around sex and sexuality. It focuses on men that donate sperm outside of a clinical context via online forums, such as Facebook groups, which they do for free. The catch though is that these men do so on a large scale as the subtitle makes clear: “4 men, 175 babies”.

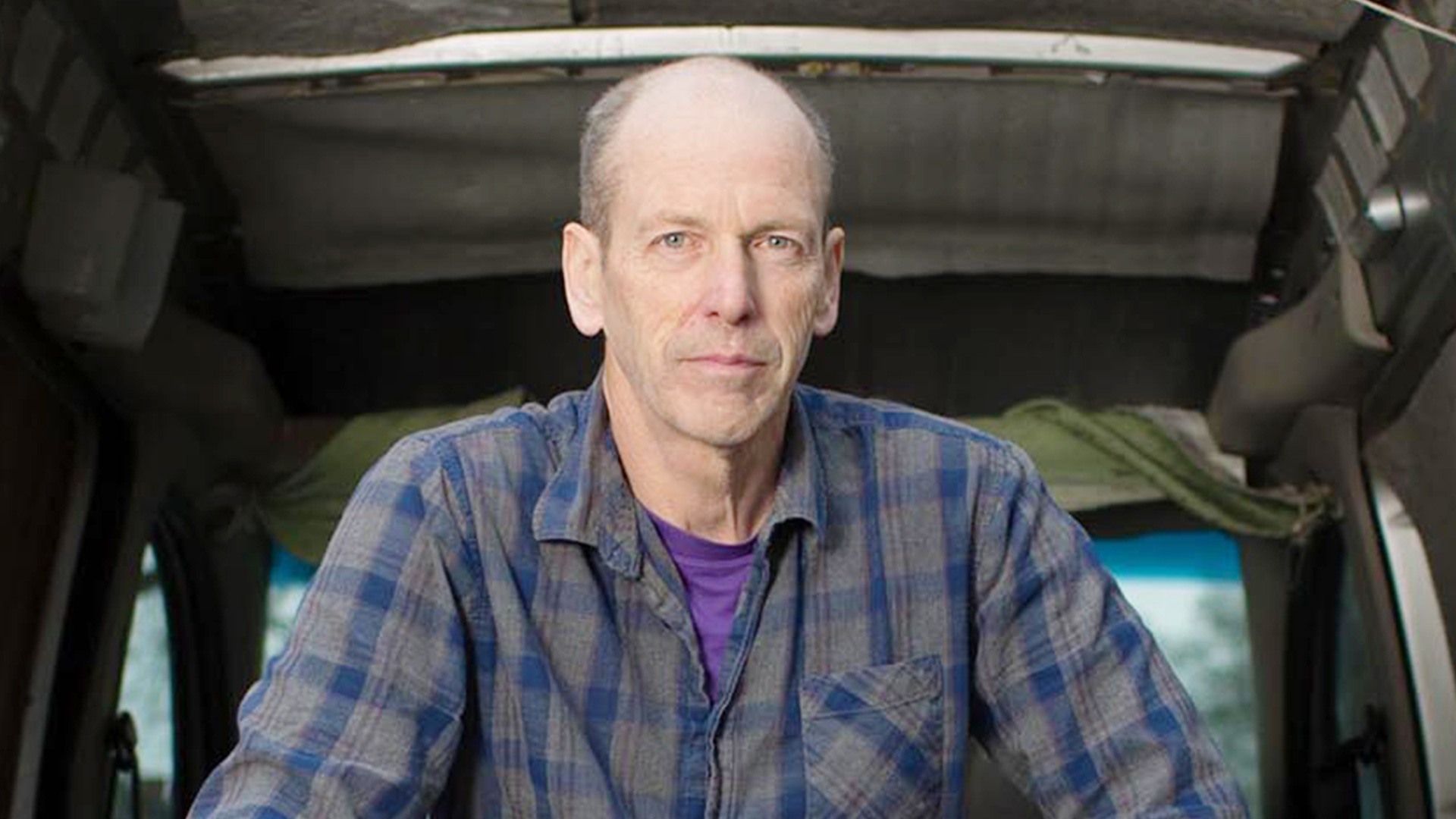

Clive, from Super Sperm Donors: 4 men, 175 babies. Taken from: https://www.channel4.com/programmes/4-men-175-babies-the-uks-super-sperm-donors

I watched in part because, given the sensational title, I was hoping the initial disgust I felt would be challenged by the documentary offering a more complex picture. There were already scandalous media reports portraying Facebook sperm donors as dangerous rogue breeders. At the start, this is what I got. Clive seems like an affable enough fellow, satisfied simply with the prospect of giving joy to others that want a baby. I was drawn in by the rhetoric of ‘gift-giving’, ‘joy and happiness’, ‘love’ and of course ‘family’. As he puts it:

“The reason I do this is purely to help people. I see the happiness that it brings and that’s enough payment in itself”

As someone who has supported women’s and queer families’ reproductive rights and who has witnessed people close to me suffer the struggle to conceive, I felt understandably drawn to his selflessness in freely gifting his own semen for others to start their own family with no strings attached. This echoed academic research portraying this practice as “an altruistic act” in which donors had to make “certain personal sacrifices and risks”.

He talks openly about his donation procedure in seemingly professional tones, while avoiding words like ‘sperm’ in favour of ‘the donation’. Essentially, he turns up to the recipient’s house, wanks into a beaker inside his own van, puts his semen into a syringe and then hands it over at their door without ever stepping foot in their house. I saw this as a sign of his thoughtfulness in serving the role of a donor, keeping himself distant from the family. He cultivated an air of being clinical, delivering on his promise to donate with no strings attached.

But then we meet Mark, who is more secretive about his donations. He lists his recipients as lesbian couples, a few single ladies and straight couples where the husband has had a vasectomy. He explains that he tried to donate at a sperm clinic but was too old and so chose to donate via this unregulated system. In contrast to Clive, Mark talks more possessively about the outcome of his donations: “To date I’ve got 54 babies born with nine ladies currently expecting” (Mark, my transcription, my emphasis). Instead of a rhetoric of selflessness, his donating came from feeling “underused” after having had his own children with his wife. He asks rhetorically “if Des O’Connor could have babies at the age of 73, why couldn’t I?” But his reasons are even more narcissistic than the facile comparison with Des O’Connor. As he explains:

“I want to reproduce with as many women as possible and pass on the genetic characteristics that I have”

This is demonstrated by a cut to him playing with one of the children produced from his donations in which he observes proudly “She’s got those wonderful blue eyes that all my babies have”.

The undertone narcissism is difficult to ignore the further we delve into the various men’s backstories and reasonings. Even the affable Clive mentioned above later shows his meticulous record keeping of every donation and pregnancy. He pulls out a map where he plots the birthplaces of each one of the babies created from his donations. We watch him drawing each dot onto his map from his accurate records and then admiring how much they cover the map. Another donor talks about getting women pregnant as similar to ‘scoring a goal’, pinning this down to a psychological “classic male focus on a number” that they can increase. Mark philosophizes:

“Procreation is a natural instinct. I think if I was a three-foot dwarf with only one eye I’d still want to spread my genetic material as far and as wide as possible”

Later the 61-year old Clive becomes worried about declining fertility when his success rate of conception appears to drop. He becomes slightly defensive, saying “in my defence” before reminding the camera that the women have fertility issues. Before the next donation he checks his sperm under a microscope with the camera rolling, exclaiming: “oh crikey! Ab-so-lutely billions of them! […] Looking here, I can’t see what the problem is, it’s certainly not me” he concludes, smiling.

Narcissism is perhaps most obvious in the ways that they deal with their own relationships to women in their lives. Clive began donating without his wife’s knowledge, but later confesses when she discovers his secret. Although she is unhappy with it, he still continues to donate to hundreds of recipients in his spare time and using their money. By contrast, Mark has not even told his wife, knowing that she would feel that it was a form of cheating. But rather than give her a choice or a say, he chooses to do this behind her back, which if not cheating sexually is still an act of dishonesty that removes her ability to be a co-decision maker. While a third unmarried man, Mitch, says that he’s had difficulties with girlfriends who couldn’t understand his abstinence, interpreting their rejection of his abstinence as a complaint about losing their ‘enjoyment’ signified by his ejaculation.

Both Clive and Mitch even use the happiness of the recipients to counter the unhappiness in the women in their lives. As Clive says: “it’s making her [his wife] unhappy. However, it’s making lots of people very happy” (emphasis in original, my transcription). Mitch explains his stance on abstinence: “why would you put two seconds of pleasure over someone’s chance of having a family?” (emphasis in original, my transcription). This echoes a classic gaslighting trick that redirects the guilt trip onto their partner and making them question whether, in fact, they are the ones who are really being selfish. I think it’s problematic to cast these as risk-taking on the part of the men and therefore chalk it up to personal sacrifice, when this fails to adequately recognise that the men make these decisions enmeshed in the lives of others who are dependent on them. Decisions made affect the whole family at a legal level at the very least. This raises interesting questions about what men’s reproductive rights are. How much ‘right’ does a woman have over her husband’s semen? And socially, is reproduction outside marriage without sex still a form of ‘cheating’? Such questions, far from being simply intellectual, have significant implications for a family’s sense of security (financially, socially, legally) and the bonds of trust and intimacy that inhere in the families we build.

The documentary doesn’t judge the men or the women and presents many sides, including the happy and grateful mothers as well as tragic stories of unsuccessful attempts. Perhaps its greatest strength is that it allows the men to present themselves, who, in their honesty and obliviousness, often say far more about themselves than they think. So while I am similarly wary of overly negative, scandalous portrayals of ‘rogue breeders’ as the researchers I mentioned above, I think we need to be more sceptical than simply taking men at their word. Few people act out of evil intent. Most of us simply try to make our way through the messiness of life, justifying ourselves after we’ve already acted, ennobling ourselves and our motivations in the process. Yet I don’t deny they are being genuine when they say they want to help. Altruism and narcissism don’t have to be mutually exclusive motivations; people are more complex than that. Still, this begs more critical attention, particularly when so many children’s lives are at stake. And while it is true that media have highlighted dramatic cases, such limit cases might have much to teach us as well, philosophically and legally. We should not dismiss them either.

Yet despite the obvious machismo and narcissism, who am I to say that this make them bad donors or even bad men? If it’s all consensual between adults, voluntarily conducted in full knowledge and everyone is happy, who am I to judge? How many parents have children for precisely the same reasons? I’ve met many narcissistic parents in my time. I’m not convinced this becomes immoral simply because it’s practiced on an industrial scale. Far more children are conceived in far less noble circumstances all the time around the world.

Nor am I convinced that better regulation of donation outside a clinic would stop these kinds of donations (although it might limit how extensive these donations are). Certain regulations can be put in place to minimize dishonest donations, but they can’t entirely screen motivations, or, even if they could screen motivations, I’m not currently convinced of arguments for banning motivations other than profit or direct benefit. This would require parents of assisted reproduction to have more barriers to reproduction than others who don’t have to question their motivations simply because they don’t need assistance in reproducing.

But this does shine a light on the gap between rapidly shifting reproductive practices with new technologies and our capacity to ascertain and judge the political and ethical rules governing these new practices at a social level. And it does raise interesting, knotty questions for me as a gender studies and cultural studies scholar about the relationship between men’s bodies and reproductive rights, between technology, the social and nature, and the question of what children’s rights are in this new era of assisted reproduction.