Academic Writing as Factory Work

As the publish or perish environment of academia intensifies and graduates are now expected to have 20 books before applying for a postdoc (or whatever equally ludicrous academic inflation now considers 'entry level' qualification for job security), and as some universities turn to points-based systems to measure and compare ‘research outputs’, a growing neoliberal academic self-help industry has emerged, promising to lift us out of our languid ways if only we followed these simple rules. 142 habits of highly successful academic authors! How to publish 52 journal articles in a year!

Within this trend, one thing I’ve increasingly encountered are academics promoting writing as a kind of factory labour: academic writing as dispassionate production lines manufacturing publications for points. In the popular ‘Pomodoro method’ you literally clock in and out of short bursts of work with alarm clocks telling you when to put the writing tools down and when to pick it up. Others suggest shorter bursts. Rather than follow an idea where it leads us, we follow an arbitrary clock. Write for only 15 mins each day or even just 10 mins each day. Writing for time-poor academics. Writing gurus appear to slay the romantic illusions that stubbornly refuse to serve our new masters: prophets (or overlords depending on your perspective) of The New Age of Academic Productivity. We are exhorted to leave inspiration, imagination and passion at the door. We're here to write, god damn it! The tongue-in-cheek title of many writing workshops and groups neatly captures this new attitude: "Shut Up and Write!"

To be clear, these techniques do work … for certain problems. If you find yourself lacking motivation or if you find yourself lacking discipline, then setting yourself clear and achievable goals to complete in short bursts of time can be very useful in helping you form writing habits and regulate your alertness. Being part of a writing group can help you feel ‘accountable’ to your writing goals. There’s much to commend these approaches. But not all writing problems are about motivation and discipline. Many academics are ‘motivated’ by high levels of precarity and the desperate belief that if only they published this one more thing they can have more secure work. Motivation is not the issue. Treating all ‘unproductive’ writers as if they were simply lacking the will to write isn’t just patronising, it also displays a severe misunderstanding of the range of writing problems that scholars/authors can encounter. It assumes that the act of writing is transparent and easy, only requiring time rather than skills development. Learning to identify new writing problems that one encounters with new phenomena or novel arguments and developing new writing solutions is a key part of academic writer development. Perhaps I’m slower than my colleagues, but such things take me much longer than 15 mins to solve.

My main concern is that this factory approach to writing is beginning to seep into academia, where it is beginning to stifle other approaches. In some writing circles, the art of writing is discouraged. Writing here become a paint-by-numbers exercise. Form no longer follows function. Indeed, function is reduced to formulaic cookie-cutter sentences that stand in for the work of learning to articulate complex argumentation unique to one’s work. Eloquence through variation is discouraged. Inventing a good turn of phrase is time consuming. Finding your voice is a non-discussion. Instead, here are some pre-made sentences. Just add info and voila! You have writing! There is a vast difference between learning rules of composition that help guide you to express your own argument, and purposefully narrowing arguments in order to fit simplistic writing rules or formulaic sentence structures.

Some teach their junior colleagues to maximise their outputs by ‘salami-slicing’ their argument. 'Don't waste all of your argument in one article when you can write two or three!' Some of us are taught to minimise our efforts by calculating how many points we get per number of words. 'This journal publishes 3000 word articles that count as a full point, but this journal published 8000 word articles that only count as half a point'. Strategise! Location, location, location! Maximise what counts as outputs; minimise effort. This is what academic 'writing' has become.

Yet this is not the writing that inspired me and drew me to academia. It’s not the writing that I loved, the writing I would devour in cafes contemplating their idiosyncratic turns of phrase, savouring their eloquence just as much as their insight. For me, good writing forges new meanings and understandings through words that transform people's relationships to themselves, to things and the world around them. It is an exploration into the unknown: the tentative, careful but insightful reaching out to others, to other places and situations, pushing against the limits of our knowledge. The act of writing can also be an exploration of the self, of finding one's voice - not just centralising authorial voice but finding a style of expression that is yours, that best conveys your ideas.

Writing invites the reader to look askance at the world, to see things differently. Writing doesn’t always have to be goal-oriented. We don’t need to always see the destination. Sometimes it is enough that you are here, with me, to start this journey together. Sometimes it is enough that we are asking this question seriously, no matter how small, with the gravitas that a world of mysteries deserves. Other times writing can be a world-making practice; the art of creating inhabitable futures for us to live better lives. Sometimes we can even get lost in these worlds, meandering and tripping into new rabbit holes. My favourite authors can give you a sense of purpose even as they remove the ground from under your feet or take you for a seemingly aimless wander while still finding meaning in it all. It's a tricky path, but it’s a wondrous opening into worlds that other writers would never dare to tread because they lack the writing skills to navigate successfully. At other times, writing can be an impassioned endeavour to call oneself and others to action, to enact justice, to fight for equality or simply to make things better for others. It might invite us to linger in our discomfort, to ask us to confront ourselves in our hypocrisies and lies. Writing can lead us to the better part of ourselves.

Not everyone shares all these senses of writing with me, and that's fine. That's what makes us different readers and different writers. But instead of academia preserving and indeed promoting diverse writing, in certain sections, which I fear are growing, we are being asked to become writing drones, spewing forth predictable article after predictable article with formulaic phrases that mimic an intellectual enquiry but lacks any of the passion and curiosity that makes it such. Zombie articles, perambulating their way across a passionless academic landscape. Is this what it means to be a modern productive academic?

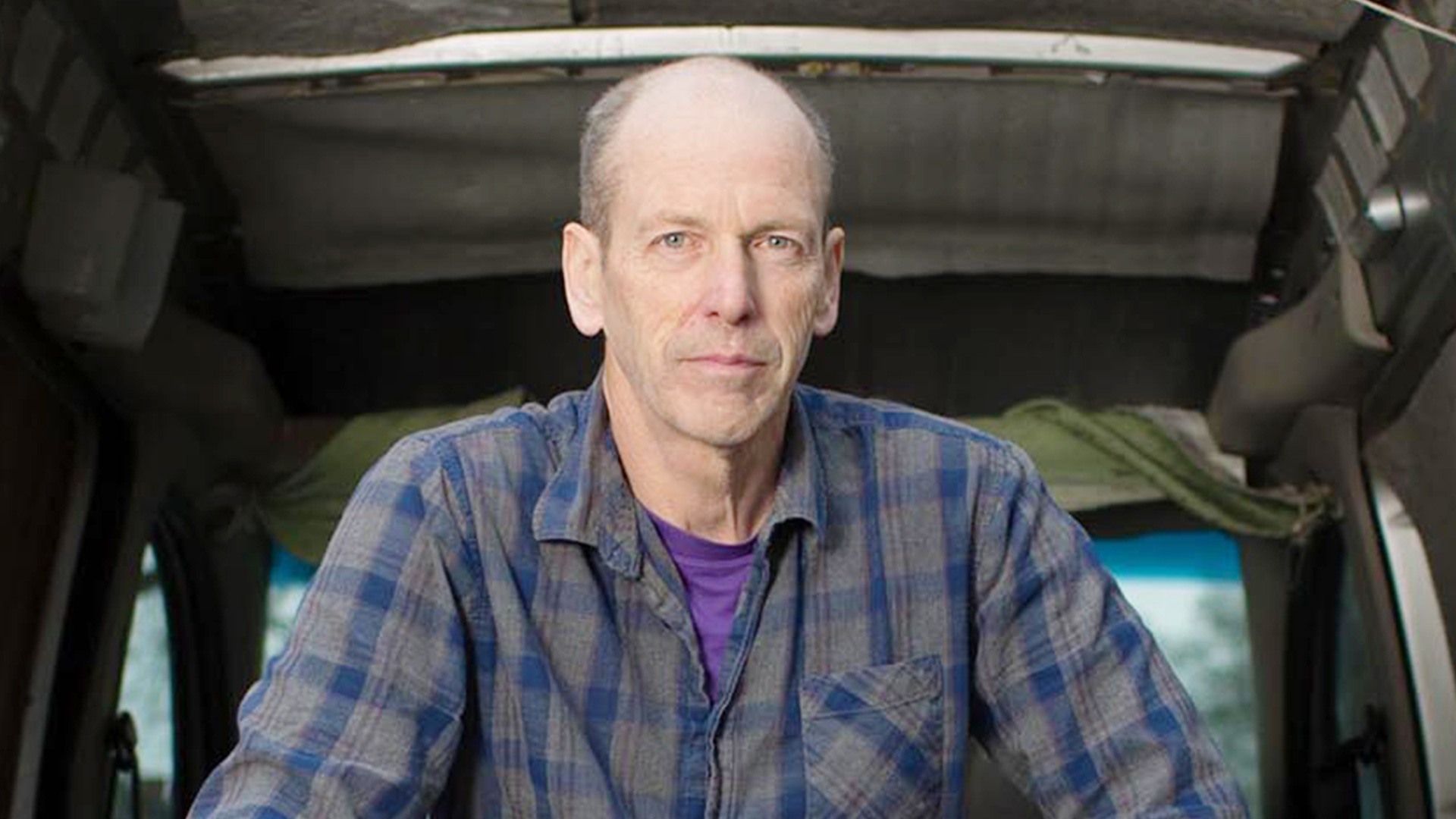

Perhaps I am, as they suggest, one of those stubborn romantics. ‘Of course, he would defend the old ways. Look at him. He's barely productive himself.’ Perhaps I will be described as an elitist that clings to a patriarchal, aristocratic model of writing best suited to upper class European men with slabs of leisure time made possible in part by their doting wives and servants. Writing is work, they insist. Idealism is a privilege we cannot afford. Sure, writing is work. I'm not denying that. But to insist that the factory is the best model for the labour of academic writing (rather than artisanship, craftsmanship, play, exploration, meditation, dialogue, experimentation, etc.) seems to be an increasingly unchallenged truth and one that limits not just our modes of expression but also our modes of inquiry.